Hirohito is one of the most recognized names in Japanese history, but it sparks curiosity for an unexpected reason—whether using it is actually banned in Japan. The short answer? No, it’s not officially banned, but cultural and historical practices make it practically nonexistent in daily use. This raises fascinating questions about the intersection of tradition, reverence, and modern culture. Understanding why the name is avoided sheds light on Japan’s deep respect for its imperial customs and the historical weight connected to Hirohito’s legacy.

Who Was Emperor Hirohito?

Emperor Hirohito, also known as Emperor Shōwa, remains a pivotal figure in Japan’s history. His reign spanned over six decades, making him one of the longest-reigning monarchs in the world. Known for his significant role during World War II and Japan’s post-war recovery, Hirohito’s legacy is deeply intertwined with monumental events in Japanese and global history.

Hirohito’s Reign from 1926 to 1989

Photo by DSD

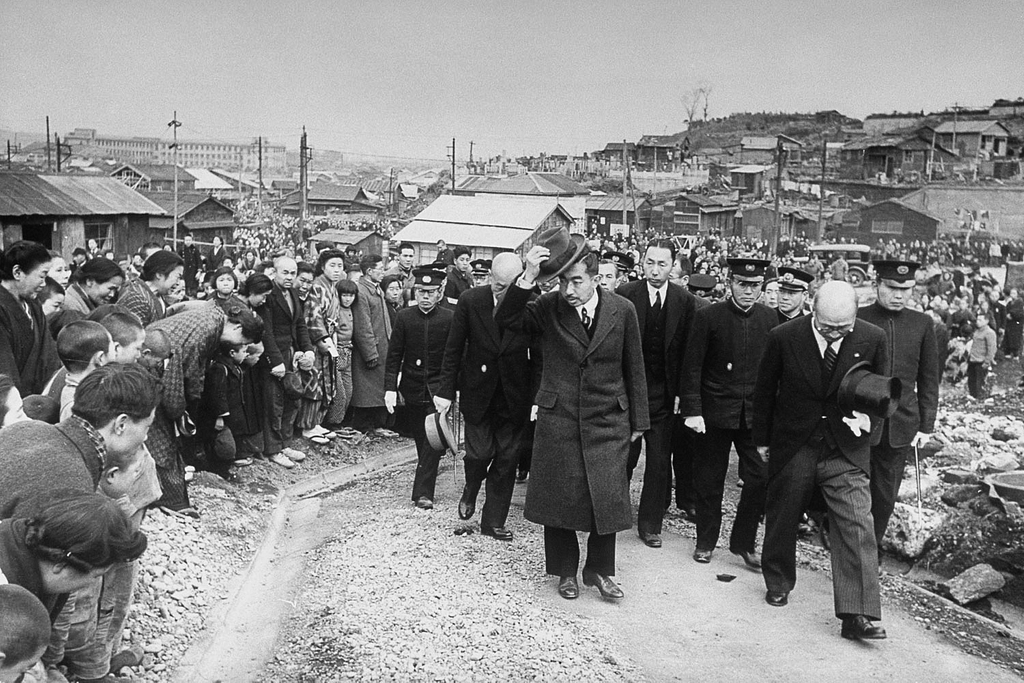

Hirohito ascended to the throne in 1926 as the Shōwa Emperor. His reign began during a time of growing political and military tensions. By the 1930s, Japan had shifted towards militarism, leading to aggressive policies of expansion and eventual involvement in World War II.

Key moments during Hirohito’s reign include:

- The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945): This conflict was a precursor to Japan’s role in World War II, marked by invasions and expansion across Asia.

- World War II: Under Hirohito’s reign, Japan launched the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which drew the United States into the war. The war ended with Japan’s defeat and the devastating atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

- Japan’s Post-War Reconstruction: Following Japan’s surrender, Hirohito played a ceremonial role in rebuilding the country. Under U.S. occupation, Japan adopted a new constitution in 1947, transforming its political landscape into a constitutional monarchy.

There is lasting debate about Hirohito’s role in Japan’s militaristic actions. Some argue he was a figurehead with limited power, while others suggest he was more involved in wartime decisions. His reign encapsulates a dramatic transition for Japan—from an imperial power to a peaceful, post-war nation.

Learn more about Hirohito’s role during these key historical moments.

Posthumous Naming and the Role in Japanese Tradition

In Japan, emperors are given posthumous names to honor their legacies. These names are often tied to the era in which they ruled. This tradition, deeply rooted in respect and reverence, reflects the cultural importance of the imperial family.

Hirohito’s posthumous name, Emperor Shōwa, follows this custom. The name “Shōwa” (昭和) symbolizes “enlightened peace,” serving as a reminder of the challenges and transformations during his lifetime. This practice underscores why calling him “Hirohito” is unusual in Japan; addressing an emperor by their personal name, especially posthumously, is considered disrespectful.

Reasons behind this custom include:

- Cultural Symbolism: The posthumous name reflects the emperor’s era and contributions. This helps frame history in both cultural and national contexts.

- Formal Etiquette: Referring to emperors by their personal names is avoided to preserve propriety. Even today, Hirohito is almost exclusively called “Emperor Shōwa” in Japan.

Explore the significance of posthumous imperial naming in Japan.

Understanding these traditions adds depth to the question, “Is the name Hirohito banned in Japan?” While it’s not legally forbidden, cultural customs and historical reverence make it rare to hear his given name in daily life.

Why Is Hirohito’s Name Rarely Used in Japan Today?

The avoidance of the name “Hirohito” in Japan is a fascinating cultural and historical practice rooted in deep traditions and sensitivities. Understanding this phenomenon requires looking at Japanese customs surrounding emperors, the weight of historical periods, and the formal naming conventions that honor their legacies.

Cultural Respect for Deceased Emperors

In Japan, referring to deceased emperors by their personal names is seen as disrespectful. Instead, posthumous names are assigned, symbolizing the era in which they reigned and their historical contributions. Hirohito, after his passing in 1989, was given the posthumous name Emperor Shōwa, which translates to “enlightened peace.” This reflects the cultural emphasis on reverence and the framing of history through imperial eras rather than personal identities.

This practice stems from broader Japanese customs around death and respect. Much like the careful rituals performed at Japanese funerals to honor the deceased (read more about Japanese funeral traditions), referring to an emperor by their personal name after death would break traditional norms. Instead, the use of their era name ensures their memory is tied to the broader historical context, rather than a singular, personal identity.

Association with Controversial Historical Periods

Hirohito’s name remains closely tied to one of Japan’s most tumultuous periods: World War II. As Emperor during the Shōwa era (1926–1989), his reign encompassed Japan’s militaristic expansion, the war itself, and the nation’s subsequent surrender and recovery. While historians debate Hirohito’s exact role in wartime decisions (explore this deeper analysis), many outside Japan associate his name with those controversial years.

This historical connection complicates the casual use of the name. In Japan, acknowledging the past while focusing on the future is important. The emphasis on his posthumous name, “Emperor Shōwa,” allows people to honor his broader legacy—his contributions to peace and modernization after the war—while distancing him from potentially divisive affiliations with wartime actions.

Use of ‘Emperor Showa’ as the Formal Reference

After Hirohito’s death, the Japanese government and media formally adopted “Emperor Shōwa” as the standard way to refer to him. This aligns with the tradition of naming eras after their reigning emperors. The “Shōwa era,” lasting from 1926 to 1989, defines a significant chapter in modern Japanese history (learn more about the Shōwa era).

In everyday conversation, the Japanese rarely mention emperors by their personal names, alive or deceased. Current and past emperors are typically referred to by their titles, such as “His Majesty the Emperor,” ensuring a respectful distance. Outside Japan, however, Western media often used Hirohito’s given name, leading to confusion about its appropriateness. This reflects differing cultural approaches to naming and respect (why the West used Hirohito’s name during WWII).

By understanding these practices, it’s clear why the name Hirohito is rarely heard today in Japan. It’s not banned but is set aside in deference to deep traditions, historical sensitivities, and formal posthumous naming conventions.

Is the Name Hirohito Banned in Japan?

While the name “Hirohito” is not officially banned in Japan, its use is heavily influenced by cultural customs and historical sensitivities. To understand this, it’s important to explore how legal frameworks and deeply rooted traditions intersect in Japanese society.

Legal Restrictions vs. Cultural Practices

Legally speaking, there are no laws in Japan prohibiting anyone from naming their child Hirohito or using the name in conversation. However, culturally, it’s virtually unheard of. Why? Japan places immense significance on respect for its imperial lineage, and there are unwritten rules around how emperors are addressed, especially after death.

In Japanese tradition, referring to an emperor by their personal name—alive or deceased—is considered disrespectful. Posthumously, emperors are known by their era name, a title that signifies the period they ruled. For Hirohito, his official posthumous name is “Emperor Shōwa,” reflecting the era of “enlightened peace” during his reign. This practice reinforces reverence and allows historical periods to be framed through broader societal milestones rather than individual personas.

For example:

- Everyday conversation avoids using the personal names of past emperors, including Hirohito.

- Even in media or historical documentation, he is commonly referred to as “Emperor Shōwa” in Japan.

This avoidance operates not from fear of legal repercussions, but from collective cultural norms that prioritize propriety and reverence for Japan’s imperial family. Outside Japan, the name Hirohito has been used freely, often due to a lack of understanding of these customs by Western cultures (learn more about Hirohito’s portrayal in Western media).

Historical Sensitivities Around the Name

The name Hirohito carries a historical weight that cannot be underestimated, especially because of his association with Japan’s wartime past. As emperor during World War II, Hirohito presided over one of Japan’s most controversial and transformative eras. While historians continue to debate the extent of his role in military decisions, his name remains a sensitive topic within Japan (explore the debate on Hirohito’s wartime influence).

This sensitivity stems from several factors:

- Legacy of World War II: For many, hearing the name “Hirohito” evokes memories of Japan’s militaristic expansion and the devastating consequences of the war. Although he played a significant role in post-war recovery, his reign is still linked to these turbulent years.

- Imperial Customs and Memory: By using his posthumous title, Emperor Shōwa, people are able to honor the broader context of his legacy while distancing themselves from the controversies tied to his personal name.

- International Perception: Outside Japan, the name Hirohito became synonymous with Japan during WWII. This association sometimes conflicts with how his legacy is framed domestically, where his contributions to rebuilding Japan are highlighted (read an analysis of Hirohito’s post-war role here).

Another layer to this is Japan’s collective preference to focus on reconciliation and future progress rather than dwell on past controversies. By anchoring his memory to “Emperor Shōwa,” Japanese society emphasizes the ideals of peace and recovery symbolized by the post-war era over the complexities of wartime actions.

In essence, while the name Hirohito isn’t banned in any legal sense, it is avoided almost entirely out of respect for deep cultural traditions and the sensitivities tied to Japan’s past. Like a silent societal agreement, this practice reflects larger values of propriety, history, and collective memory in Japan.

Comparison to Other Notable Historical Figures

Throughout history, certain names have become stigmatized due to their association with controversial individuals or events. While the name “Hirohito” is not banned in Japan, its near absence from everyday conversation raises questions that invite comparisons with global practices and Japan’s unique cultural norms.

Global Practices in Naming Controversy

Around the world, names tied to controversial figures often face strong reactions and, in some cases, outright restrictions. These decisions, grounded in social ethics or legal regulations, highlight the discomfort surrounding such names.

- Adolf Hitler: Perhaps the most infamous example, the name Adolf Hitler is virtually extinct in modern Germany. Associating with this name carries a significant stigma due to Hitler’s role in World War II and the Holocaust. While not banned outright, naming a child Hitler would likely attract public and legal scrutiny in several countries, including Germany and Austria (source). In the U.S., a New Jersey couple faced custody issues after naming their child Adolf Hitler, which demonstrates how society treats such cases as beyond cultural norms (read more).

- Other Examples: Laws in countries like Portugal and Saudi Arabia have prohibited certain names deemed offensive to cultural, moral, or political standards. These restrictions aim to maintain national pride or avoid provoking historical tensions (learn more).

Globally, this avoidance reflects a form of “societal auto-correction.” Even without explicit bans, people tend to steer clear of names associated with highly sensitive histories. It’s an unspoken rule, reinforced by collective memory and cultural values.

How Japan’s Approach Differs

Japan’s approach to naming customs is deeply embedded in a tradition of respect and reverence, especially when it involves figures of historical significance like Emperor Hirohito. Unlike other nations, Japan doesn’t rely on legal measures to guide these practices—it’s all about cultural propriety.

- Respect for Elders and Figures of Authority: In Japan, there’s an intrinsic reverence for hierarchical relationships, whether among family, coworkers, or historical figures. Addressing someone by their given name, especially in formal contexts, can seem overly casual or even disrespectful. When it comes to emperors, avoiding their personal names after death honors their legacy (source).

- Role of Posthumous Names: As with Hirohito being referred to as Emperor Shōwa, posthumous names are not just symbolic but also practical. They allow society to focus on the larger era and its significance rather than the individual’s actions alone. This shift helps maintain harmony within the national narrative, sidestepping potential conflicts tied to personal controversies (learn more).

- No Legal Enforcement, Just Tradition: In many cases worldwide, avoiding a name might be encouraged by laws or societal backlash. In Japan, it’s simply an unwritten cultural understanding. The weight of tradition and propriety is often enough to guide behavior.

Japan chooses reverence over restriction. While the name “Hirohito” isn’t banned, its avoidance is a silent acknowledgment of respect—a key difference from how other nations handle historical shadows. Instead of codified laws, social customs serve as the guiding framework. This reflects Japan’s focus on preserving harmony and cultural memory without coercion.

Modern-Day Perspectives on Hirohito

Discussing Emperor Hirohito, or Emperor Shōwa as he is known in Japan posthumously, brings out a complex blend of academic debates and cultural perceptions. His role during the Shōwa era (1926-1989) continues to be analyzed and reevaluated, especially against the backdrop of his wartime actions and later contributions to Japan’s reconstruction. In Japan today, Hirohito’s legacy is both celebrated and critiqued, reflecting the diverse perspectives held by the public and scholars.

Academic and Cultural Debates

Hirohito’s role in Japan’s wartime history remains a hot topic in scholarly circles. Some historians argue that he was merely a symbolic figurehead with limited control over Japan’s military decisions. Others suggest he wielded more influence than publicly admitted, raising questions about his accountability for Japan’s militaristic expansions and actions during World War II.

Key areas of contention include:

- The Extent of His Power: While Japan’s military leaders, such as Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, were outwardly responsible for policy decisions, declassified documents and testimonies indicate Hirohito might have endorsed or, at the very least, been privy to critical military strategies. However, debates continue about how deeply involved he was in decisions like the attack on Pearl Harbor.

- Post-War Narratives: After Japan’s defeat, the Allied Occupation under General Douglas MacArthur chose to portray Hirohito as a pacifist figure. This crafted narrative aimed to stabilize Japan post-war and ensure smooth political transitions (read more about Hirohito’s role during these times).

- Cultural Gaps in Accountability: In Japan, Hirohito is often seen as a unifying figure who guided the nation through reconstruction during the post-war years. However, international historians often focus more on his tacit involvement in Japan’s aggressive wartime policies (explore deeper analysis here).

The academic debate surrounding Hirohito illustrates the challenges of reconciling Japan’s wartime legacy with its post-war achievements. For many, this debate represents more than historical questioning—it’s a struggle to define Hirohito’s role in shaping Japan on a global stage.

Photo by Evgeny Tchebotarev

Public Sentiment and Media Representation

How does the Japanese public perceive Hirohito today? The conversation in Japan often leans more toward his symbolic role as the Shōwa Emperor rather than his given name, which is rarely ever used. Public sentiment paints a picture of both reverence and distance, depending on the age group and cultural setting.

- Generational Views: For older Japanese citizens, Hirohito symbolized stability during turbulent times. They remember him more for his televised announcement of surrender or his presence in Japan’s remarkable reconstruction efforts. For younger generations, Hirohito is often a historical figure taught in school rather than a personal connection.

- Media and Education: In Japanese media, Hirohito’s wartime role is typically downplayed. Documentaries and textbooks often focus on his post-war contributions to peace and Japan’s modernization rather than scrutinizing his involvement in military conflicts. This contrasts with portrayals in Western media, where his wartime relevance is emphasized (read more on media depictions).

- War Museums and Public Memory: War-related museums in Japan approach the topic of Hirohito delicately, often omitting direct references to his wartime decision-making. These omissions reflect a broader cultural tendency to focus on reconciliation and progress rather than the intricacies of blame (see discussions on museum portrayals).

In many ways, Hirohito’s image today is shaped as much by what is left unsaid as by what is remembered. By framing him as Emperor Shōwa, Japan emphasizes his role as a national symbol rather than an individual actor, preserving an image of harmony while sidestepping deeply rooted controversies.

Conclusion

The name “Hirohito” isn’t legally banned in Japan, but using it goes against deeply ingrained traditions and cultural norms. Posthumous naming customs, historical sensitivities, and reverence for Japan’s imperial family all contribute to its rare usage. Referring to Emperor Hirohito as “Emperor Shōwa” helps honor his broader legacy while respecting traditions that distance personal names from public memory.

This practice reflects Japan’s focus on harmony and respect over strict rules. It’s a reminder of how history, culture, and customs shape language and the way we honor the past.